1 Introduction: What’s the Difference?

Have you ever looked at two program descriptions and wondered how equivalent they are–or, conversely, how they can be distinguished?

In concurrency theory, one runs into this problem often, for instance, when analyzing models of distributed algorithms or when devising examples for teaching. More mundanely, the question occurs every time that someone rewrites a program part and hopes for it to still do its job.

My first formal encounter with the question of behavioral equivalence came when I was implementing a translation from the process algebra Timed CSP to Timed Automata.1 How to tell whether the translation would properly honor the semantics of the two formalisms? Did it translate CSP terms to automata with the same meaning? Even the definition of the question is tricky, as there are different notions of what counts as “same meaning” in the semantics of programs.

1 My job as student research assistant was to bridge between the tools FDR2 and UPPAAL for Göthel (2012). The previous work had serious flaws: One approach introduced spurious deadlocks to the model, the other was unable to handle nesting of choices and parallel composition. Clearly, we had to change the encoding!

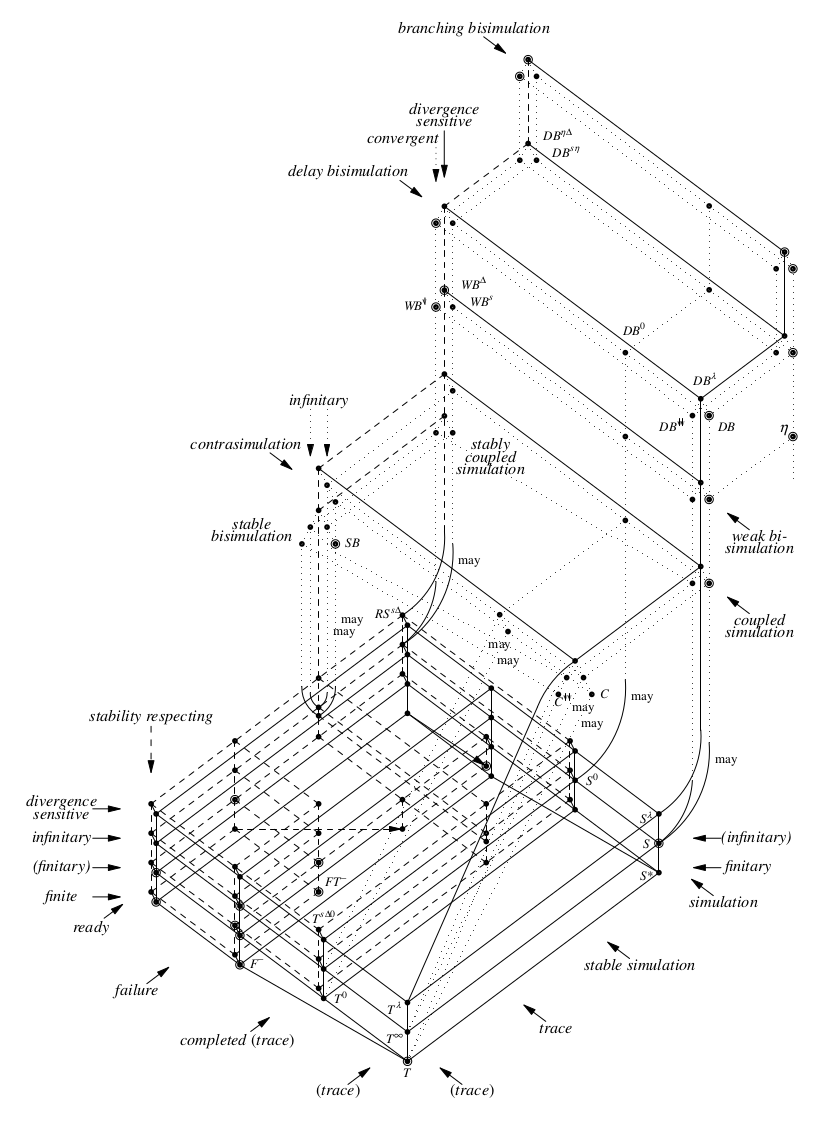

I then took my very first look into seminal work on the landscape of process equivalences: the “linear-time–branching-time spectrum” by van Glabbeek (1990, 1993; 2001 with a combined 2500 citations on Google Scholar). A central figure, reproduced in Figure 1.1, mesmerized me. So many equivalences! But, how to find out for a given pair of processes which of the many equivalences apply? Over the years, I have learned that others, too, have run into the not-quite-straightforward question which equivalences hold: For instance, Nestmann & Pierce (2000) thinking about process algebra encodings and Bell (2013) verifying compiler optimizations. We share an itch.

Our problem can abstractly be summarized as follows:

How does one conveniently decide for a pair of systems which notions from a spectrum of behavioral equivalences equate the two?

The above question serves as the research question of this thesis. We want to enable future researchers to tap into the wisdom of the linear-time–branching-time spectrum and to easily determine what equivalences fit their models.

1.1 Linear-Time–Branching-Time Spectroscopy

To illustrate the problem, let us look at an example that we will be able to solve via tool support at the end of the thesis in Section 8.1.2. It includes numerous concepts that we are going to define and discuss more deeply on our way there.

Example 1.1 (Verifying Peterson’s mutual exclusion) Many verification tasks can be understood along the lines of “how equivalent” two models are. The models can usually be expressed as labeled transition systems, that is, as graphs where nodes represent program states and edges represent transitions between them, labeled by actions.

Figure 1.2 replicates a standard example, known, for instance, from the textbook Reactive systems (Aceto et al., 2007): The left-hand side gives a graph specification of mutual exclusion \mathsf{Mx} as two users \mathsf{A} and \mathsf{B} entering their critical section \mathsf{ec_A} / \mathsf{ec_B} and leaving \mathsf{lc_A} / \mathsf{lc_B} before the other may enter. The right-hand side shows the transition system of Peterson’s mutual exclusion algorithm (1981) starting in \mathsf{Pe}, with internal steps \color{gray}\xrightarrow{\smash{\raisebox{-2pt}{$\scriptstyle{}$}}} due to the coordination that needs to happen.2 For \mathsf{Pe} to faithfully implement mutual exclusion, it should behave somewhat similarly to \mathsf{Mx}.

2 To fit on the page, \mathsf{Pe} is minimized by a behavioral equivalence that will be important later on: stability-respecting branching bisimilarity.

In Section 8.1.2, we will regard how the transitions of \mathsf{Pe} derive from pseudocode and formal model.

Semantics in concurrent models must treat nondeterminism and internal steps in some way. As we will see throughout this thesis, setting the degree to which nondeterminism counts induces equivalence notions with subtle differences. In the example, \mathsf{Pe} and \mathsf{Mx} weakly simulate each other, intuitively meaning that a tree of options passing over internal activity from one process can be matched by a similar tree of the other. This implies that they have the same weak traces, that is, matching paths. However, they are not weakly bi-similar, which would require a higher degree of symmetry than mutual similarity, namely, matching absence of options. There are many more such notions, which can be incomparable in how they relate processes. In our example, one might wonder: Are there notions relating \mathsf{Pe} and \mathsf{Mx} besides mutual weak similarity?

State of the art. For many of the existing behavioral preorders and equivalences, there are various algorithms and implementations to decide whether processes are equivalent (see Garavel & Lang, 2022 for a survey). So, it would be an option to throw an array of algorithms on the transition systems of Example 1.1. For example, let us pick out stable failures and contrasimilarity, which are close to weak similarity in Figure 1.1. CAAL (Andersen et al., 2015) could establish mutual weak similarity, but does not support the other notions. mCRL2 (Bunte et al., 2019; Groote & Mousavi, 2014) would rule out stable-failure equivalence. But for contrasimilarity, we would need to implement our own solution because there is no tool supporting it. Combining different tools and algorithms like this is tiresome and prone to subtle errors. It would be desirable to treat the question in just one algorithm!

Our offer. This thesis describes how to decide all equivalences in one uniform approach based on energy games, which is easily implemented in tools.

As we will discuss in more detail in Section 8.1.2, our accompanying tool equiv.io answers the question which equivalences apply for Example 1.1 in a small query. Here is an excerpt:

Pe = (A1 | B1 | TurnA | ReadyAf | ReadyBf)

\ {readyAf, readyAt, setReadyAf, setReadyAt, readyBf, readyBt,

setReadyBf, setReadyBt, turnA, turnB, setTurnA, setTurnB}

Mx = ecA.lcA.Mx + ecB.lcB.Mx

@compareSilent Pe, MxThis query leads to the output in Figure 1.3,3 which is to be understood as an interactive version of the linear-time–branching-time spectrum of Figure 1.1.

3 This thesis often provides snippets for models on equiv.io. You can examine and modify the example models by clicking on the links reading Interactive model on equiv.io.

The big blue circle in Figure 1.3 indicates that weak simulation indeed is the most specific equivalence to equate \mathsf{Pe} and \mathsf{Mx}. Lines mean that the notion at the top implies the one below. Blue half-circles

indicate preordering in only from blue to red side. For instance, \mathsf{Pe} is preordered to \mathsf{Mx} with respect to two more specific notions, namely \eta-simulation and stable simulation (and notions below). Intuitively, this means that \mathsf{Pe} implements \mathsf{Mx} more faithfully than pure weak similarity would demand. Red triangles

mark distinctions.

By running one simple algorithm, the tool decides twenty-six equivalence (and preorder) problems on \mathsf{Pe} and \mathsf{Mx} (in about 150 ms on my laptop).

Spectroscopy analogy. How does the tool decide so many equivalences in one shot? The key are van Glabbeek’s “linear-time–branching-time spectrum” papers on comparative concurrency semantics (1990, 1993). They treat a zoo of distinct qualitative questions of the form “Are processes p and q equivalent with respect to notion N?”, where N would, for example, be trace or bisimulation equivalence. The papers unveil an underlying structure where equivalences can easily be compared with respect to their distinctive power. This is analogous to the spectrum of light where seemingly qualitative properties (“The light is blue / green / red.”) happen to be quantitative (“The distribution of wavelengths peaks at 460 / 550 / 630~\mathrm{nm}.”).

For light (i.e. electromagnetic radiation), the mix of wavelengths can be determined through a process called spectroscopy. So, we could reframe the question behind this thesis also:

If there are “linear-time–branching time spectra,” does this mean that there also is some kind of “linear-time–branching-time spectroscopy”?

The difference that this thesis makes. We answer the spectroscopy question positively, which is the key step to tackle our research question: One can compute what mix of (in-)distinguishabilities exists between a pair of finite-state processes, and this places the two on a spectrum of equivalences. We thus turn a set of qualitative equivalence problems into one quantitative problem of how equivalent two systems are. This amounts to an abstract form of subtraction between programs, determining what kinds of differences an outside examiner might observe. Thereby, one algorithm works for all of a spectrum.

1.2 This Thesis

At the core, this thesis presents an algorithm to decide all behavioral equivalences at once for varying spectra of equivalence using energy games to limit possible distinctions through attacker budgets. More precisely, we make the following contributions, each coming with a “side quest:”

- Chapter 2 lays some foundations and makes precise how bisimulation games relate to grammars of distinguishing formulas from Hennessy–Milner modal logic.

- Main result: Attacker strategies in the bisimulation game \mathcal{G}_{\mathrm{B}} correspond to distinguishing formulas in a subset \smash{\mathcal{O}^{}_{\mathrm{\smash{\lfloor B \rfloor}}}} of modal logic \mathsf{HML} (Theorem 2.3).

- Side quest: Certifying algorithms to check equivalences.

- Chapter 3 shows how to understand the strong linear-time–branching-time spectrum quantitatively and formalizes the spectroscopy problem.

- Main result: The spectroscopy problem (Problem 3.1) is \textsf{PSPACE}-hard for the strong spectrum \mathbf{N}^\mathsf{strong}.

- Side quest: Equivalence checking as subtraction.

- Chapter 4 introduces the approach of characterizing equivalence spectra through energy games and how to decide such games.

- Main result: The preorder and equivalence problems in the \textsf{P}-easy part of the strong spectrum \mathbf{N}^\mathsf{peasy} are characterized by an energy game version of the bisimulation game {\mathcal{G}_{\mathrm{B}}^{\smash{🗲 }}} (Theorem 4.1).

- Side quest: Deciding Galois energy games (Problem 4.1).

- Chapter 5 applies the approach to decide the whole strong spectrum through one game for linear-time–branching-time spectroscopy.

- Main result: The strong spectroscopy game \mathcal{G}_{\triangle} covers the strong spectrum \mathbf{N}^\mathsf{strong} (Theorem 5.1) in exponential time.

- Side quest: Deriving efficient individual equivalence checkers.

- Chapter 6 recharts the weak spectrum of equivalences accounting for silent steps to fit our game approach.

- Main result: The Hennessy–Milner logic subset \mathsf{HML}_{\mathsf{SRBB}} characterizes stability-respecting branching bisimilarity (Theorem 6.1), and its sublogics describe the weak spectrum \mathbf{N}^\mathsf{weak}.

- Side quest: Case studies in concurrency theory research.

- Chapter 7 adapts the game for the weak spectrum of equivalences.

- Main result: The weak spectroscopy game \mathcal{G}_{\nabla} characterizes the weak spectrum \mathbf{N}^\mathsf{weak} (Theorem 7.1).

- Side quest: Isabelle/HOL formalization.

- Chapter 8 showcases four implementations to conveniently perform equivalence spectroscopies in web browsers and reports some benchmarking results.

- Main result: Our approach is more general than what is usually found in tools and can compete with algorithms for simulation-like notions.

- Side quest: Analyzing Peterson’s mutual exclusion protocol.

Each chapter ends with a discussion of its position in the context of the thesis and of related work. Chapter 9 recapitulates how the thesis ascends through a hierarchy of game characterizations and considers the wider picture. Recurring symbols can be looked up under Notation.

Figure 1.4 gives an overview of how parts of this thesis build upon each other. An example of how to read the figure: Chapter 4 describes the approach to frame equivalence problems as energy games. It builds on a part of the modal characterization for the strong spectrum in Chapter 3 and on game theory from Chapter 2, which is adapted through energy games.

Not this thesis. We limit ourselves to the relevant parts of the strong spectrum (van Glabbeek, 1990) and the weak spectrum (van Glabbeek, 1993). For instance, this excludes questions around value-passing, open/late/early bisimilarities, and barbed congruences on the \pi-calculus (cf. Sangiorgi, 1996). Also, we do not consider timed or probabilistic equivalences (cf. Baier et al., 2020), nor behavioral distances (Fahrenberg & Legay, 2014). Neither do we aim to re-survey behavioral equivalences in encyclopedic detail, which means that several notions are covered without a detailed discussion of their features and merits.

1.3 Artifacts and Papers

This thesis ties together the work of several publications. It is written to be understandable on its own. For details, we typically refer to the original publications or to other artifacts for implementation and machine-checked proofs.

Publications. The following five publications fuel the thesis:

- “Deciding all behavioral equivalences at once: A game for linear-time–branching-time spectroscopy” (LMCS 2022, with Nestmann & Jansen) introduces the spectroscopy problem and the core idea to decide the whole strong spectrum using games that search trees of possible distinguishing formulas. (Conference version: TACAS 2021)

- “Process equivalence problems as energy games” (CAV 2023a) makes a big technical leap by using energy games, which removes the necessity for explicit formula construction. (Tech report: arXiv 2023b)

- “Galois Energy Games: To Solve All Kinds of Quantitative Reachability Problems” (CONCUR 2025, with Lemke) generalizes and formalizes the decision procedure of my energy game model. (Lemke’s Isabelle/HOL theory: AFP 2025)

- “Characterizing contrasimilarity through games, modal logic, and complexity” (Information & Computation 2024, with Montanari) closes gaps in the weak spectrum of equivalences for complexity, games, and their links to modal logics. (Isabelle/HOL theory: AFP 2023; Workshop version: EXPRESS/SOS 2021)

- “One energy game for the spectrum between branching bisimilarity and weak trace semantics” (EXPRESS/SOS 2024, with Jansen) adapts the spectroscopy approach for the weak spectrum. (Journal version: Preprint 2025; Isabelle/HOL theory: AFP 2025)

Prototype. The algorithms of this thesis have been validated through a Scala prototype implementation. Throughout the thesis, many examples come with listings of equiv.io input and a link to try it out in the browser. You have already seen one such example for Peterson’s mutex in Section 1.1. Section 8.1.1 explains the usage of equiv.io. The source is available openly on https://github.com/benkeks/equivalence-fiddle.

Isabelle formalization. In order to relieve the document of technical proofs, these are contained in machine-checkable Isabelle/HOL theories archived on https://proofs.equiv.io/. They are split into two Isabelle sessions:

- “The weak spectroscopy game to characterize behavioral equivalences” formalizes the core results of Chapter 6 and Chapter 7: https://proofs.equiv.io/AFP/Weak_Spectroscopy/. The theory (Barthel et al., 2025) is archived in the Archive of Formal Proofs and has been developed together with TU Berlin students Barthel, Hübner, Lemke, Mattes, and Mollenkopf. Also, many theorems of earlier chapters can be understood to be supported by the formalization.

- Supplementatry proofs to support Chapter 2 and Chapter 3 are sorted under: https://proofs.equiv.io/AFP/Lineartime_Branchingtime_Spectrum_I/.

Student theses. Some parts of this thesis strongly rely on student work that I have supervised, in particular, on the following theses:

- Trzeciakiewicz (2021): “Linear-time–branching-time spectroscopy as an educational web browser game” provides a computer game version of the spectroscopy procedure to be discussed in Section 8.2.1.

- Ozegowski (2023): “Integration eines generischen Äquivalenzprüfers in CAAL” extends the Concurrency Workbench Aalborg Edition with a spectroscopy feature, reported in Section 8.2.2, extended by Straßnick & Ozegowski (2024).

- Mattes (2024): “Measuring expressive power of HML formulas in Isabelle/HOL” proves the approach to modal characterization of Section 3.2.

- Vogel (2024): “Accelerating process equivalence energy games using WebGPU,” topic of Section 8.2.3, allows massive parallelization of key parts of our algorithm on the GPU.

- Lemke (2024): “A formal proof of decidability of multi-weighted declining energy games” formalizes the Galois energy games of Section 4.3.

Other publications. My prior publications are only indirectly connected to this PhD thesis. Still, they lead me to topics and techniques:

- Bisping, Brodmann, Jungnickel, Rickmann, Seidler, Stüber, Wilhelm-Weidner, Peters, Nestmann (ITP 2016): “Mechanical verification of a constructive proof for FLP.”

- Bisping & Nestmann (TACAS 2019): “Computing coupled similarity.”

- Bisping, Nestmann, Peters (Acta Informatica 2020): “Coupled similarity: The first 32 years.”

Other student theses. During this research project, I have also supervised several other Bachelor theses, many of which played important roles in shaping the research. Although most of them do not appear directly on the following pages, I want to acknowledge the students’ vital contributions to this research.

- Peacock (2020): “Process equivalences as a video game.”

- Lê (2020): “Implementing coupled similarity as an automated checker for mCRL2.”

- Wrusch (2020): “Ein Computerspiel zum Erlernen von Verhaltensäquivalenzen.”

- Reichert (2020): “Visualising and model checking counterfactuals.”

- Wittig (2020): “Charting the jungle of process calculi encodings.”

- Bulik (2021): “Statically analysing inter-process communication in Elixir programs.”

- Montanari (2021): “Kontrasimulation als Spiel.”

- Pohlmann (2021): “Reducing strong reactive bisimilarity to strong bisimilarity.”

- England (2021): “HML synthesis of distinguished processes.”

- Duong (2022): “Developing an educational tool for linear-time–branching-time spectroscopy.”

- Alshukairi (2022): “Automatisierte Reduktion von reaktiver zu starker Bisimilarität.”

- Adler (2022): “Simulation fehlertoleranter Konsensalgorithmen in Hash.ai.”

- Sandt (2022): “A video game about reactive bisimilarity.”

- Lönne (2023): “An educational computer game about counterfactual truth conditions.”

- Hauschild (2023): “Nonlinear counterfactuals in Isabelle/HOL.”

- Stöcker (2024): “Higher-order diadic µ-calculus–An efficient framework for checking process equivalences?”

- Kurzan (2024): “Implementierung eines Contrasimilarity-Checkers für mCRL2.”

- Watermann (2025): “User-friendly web application for high-performance process equivalence checking.”

- Lifante (2025): “Automating legal reasoning in Isabelle/HOL: An embedding of logics for legal dynamics.”

This thesis itself. This document itself is created using Quarto (2025). Its HTML version is deployed to https://generalized-equivalence-checking.equiv.io/. One can find its source on https://github.com/benkeks/generalized-equivalence-checking/.

And of course, one can just continue reading it right here. In Chapter 2, we will dive into the formal description of equivalence and difference in program behavior, and start building a game framework that lets us solve our problem of generalized equivalence checking in one shot.